The Quincentennial Foundation Museum of Turkish Jews is side by side with the Neve Shalom Synagogue in Galata. I participated in the European Day of Jewish Culture event that was held here on November 27. This special day is celebrated in several cities in Europe since 1999 and in Turkey since 2001 and Jewish culture is promoted through various activities and events. I was highly impressed by this experience and I made a few more visits to the museum afterwards. I want to share my observations, what I have learned and felt. On the posters and brochures of the event it reads: “Who is this Jewish friend?” I think the word “friend” here refers both to the person who reads this and the Jews. So, let’s find out…

The museum was first opened on November 25, 2001 inside the Zülfaris Synagogue in Galata and it was moved to its current location in January 2016. It provides very valuable information about the culture of Turkish Jews who have been living in this land for centuries, their interactions with the Ottoman/Turkish culture and the contributions they have made to our society.

While it is not known exactly since when Jews have been living in Anatolia, it can be understood from the archeological ruins that they have been here since the 4th century BC. The oldest synagogue that has survived to this day in Anatolia dates back to the 3rd century and it is in the ancient city of Sardes in Manisa. In general, Jews lived in peace in Anatolian Seljuk State, Anatolian Turkish Beyliks and Ottoman Empire and they have had good relations with the Turks throughout the history.

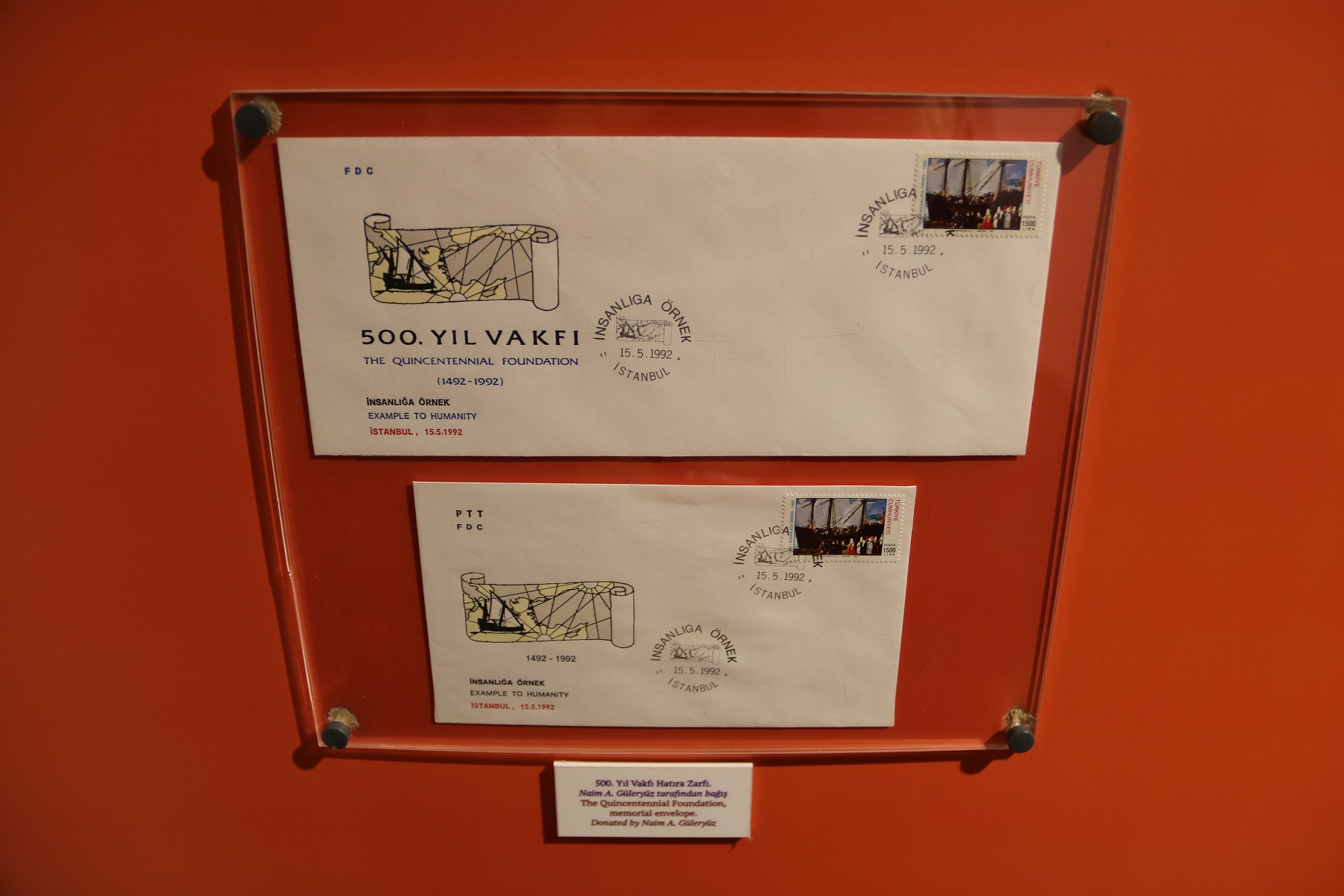

Today the majority of the Jews living in Turkey are Sephardic Jews and their arrival to this land dates back to 1492. I learned that the word “Sephardic” means Spanish or Spain in Hebrew. Spanish Jews who escaped from the King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella’s expulsion edict and the Spanish Inqusition, came all the way to the Ottoman Empire upon the invitation of Sultan II. Bayezid. Spanish Jews who were forced to leave their country by August 2, 1492, left everything behind and settled in their new land which welcomed them. The number of Jews emigrated in this period is thought to be around 120 thousand. It is known that II. Bayezid said the following words for King Ferdinand: “You venture to call Ferdinand a wise ruler, he who has impoverished his own country and enriched mine!”. And what he said really came true. Spanish Jews, with their language, culture, knowledge, experiences and occupational skills, brought richness to the Ottomans and contributed to the development of the empire.

In the museum, one of the things that impressed me the most, was the section about what Sephardic Jews brought to this land. Here, I learned that they brought artichoke, boyoz (a type of pastry), marzipan (almond paste) and pandispanya (yellow cake), silkworm breeding/silk culture, copper craft and tanning.

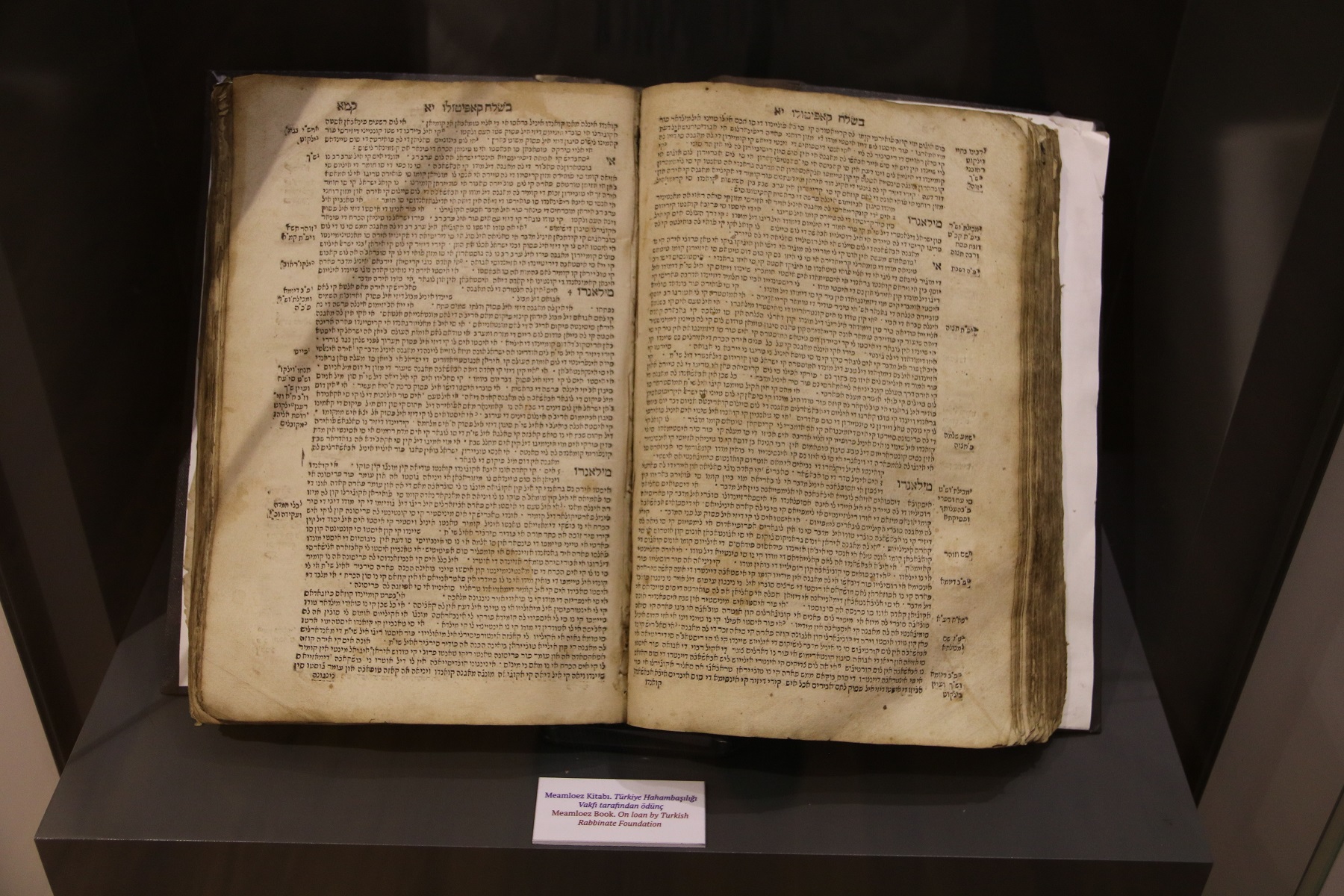

Moreover, they were the first to bring printing machines to the Ottoman Empire and founded a printing house in 1493. The year in which İbrahim Müteferrika, the first person who published a book in Turkish in the history, published the first book was 1729. Beginning from 1493, in the atmosphere of religious freedom in the Ottoman Empire, the number of printing houses increased and religious books in Hebrew were printed and sold easily.

Jews served as ambassadors in European countries. They were doctors of the Sultan and his family in the Topkapı Palace. A sword which belonged to David Hayon who worked as dentist in the palace, is exhibited in the museum.

In the museum, you can get information about the Jewish symbols, rituals, holidays and customs. One of the most important symbols of Judaism, Menorah, is a seven-branched candelabrum that symbolizes God’s creation of the universe and humans in seven days. According to the Kashrut rules which has the principle of both eating healthy and separating what is pure from what is not pure, single shank animals such as horse, donkey and pigs are not eaten. Meat and dairy are not eaten together. Religious people wait for six hours while in Europe in general they wait for two hours to pass in between. Religious Jews use separate forks and spoons for meat and dairy products.

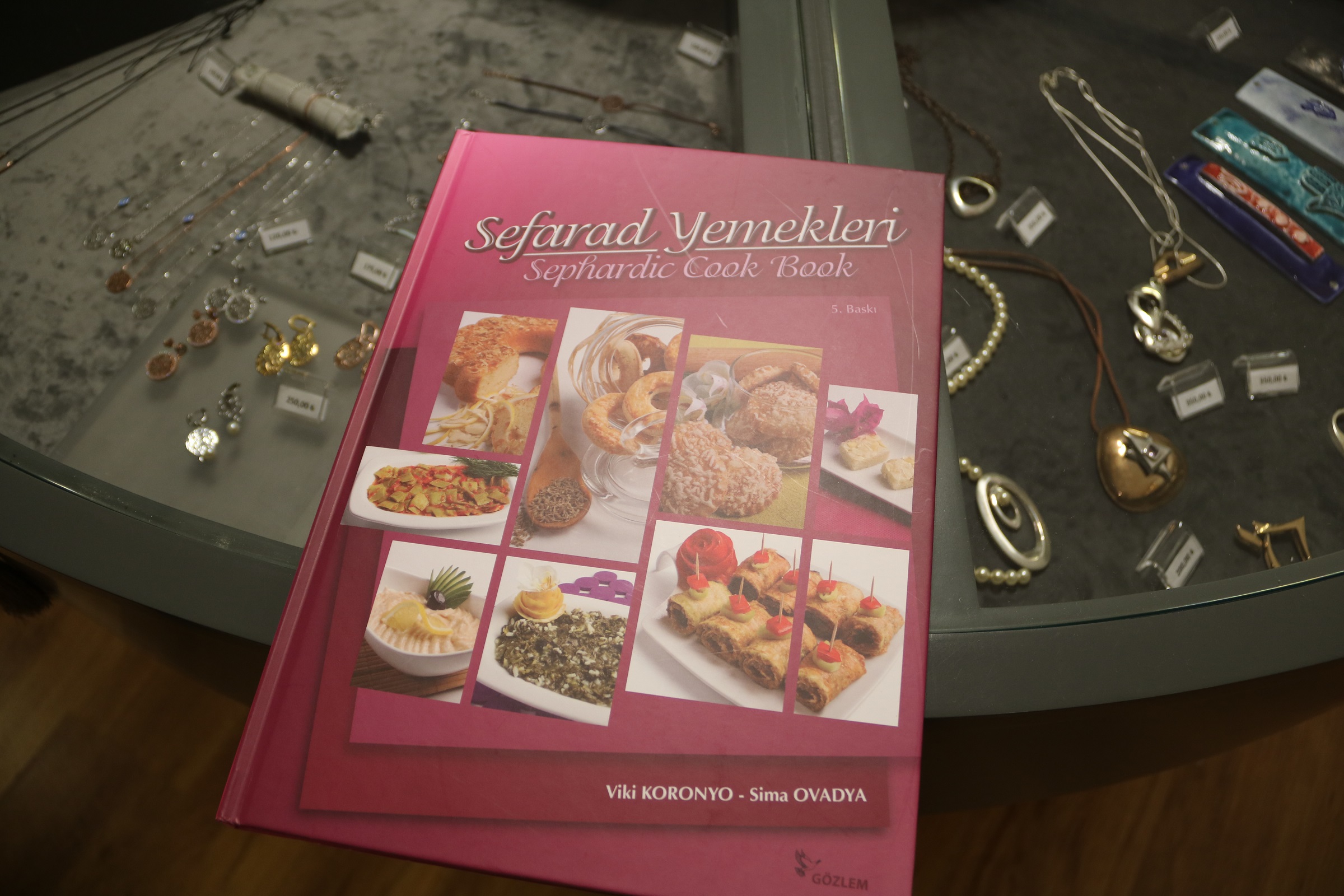

In the museum, from a touch screen you can read the recipes of some Sephardic dishes and send them to yourself or someone else via email. On November 27, we tasted Sephardic food and I especially liked the “borekitas” which is made with eggplants or patatoes.

In the museum, you can get information on the Turkish Jews who stand out with their success in various fields from sports and politics to academia and arts and their contributions to the society. In the field of politics, I learned that Cefi Kamhi served as a Member of the Parliament from Istanbul between 1995-99. After him, there were no Jews who stand out in the field of politics. There is also information given on Jews who lost their lives for our country in the Turkish War of Independence, the Turkish diplomats who saved the lives of Jews from the Nazis in the Second World War, and about the academicians who escaped from Germany and Austria in the same period, came to universities in Istanbul and Ankara upon Atatürk’s invitation and made valuable contributions to the education of Turkish students.

On the touch screen that tells about the important events from 1930 until today, information and photos on the Struma disaster (1942) and the terrorist attacks to the Neve Shalom Synagogue are shown with the hope that these shameful events for humanity will not ever happen again. You can also see the examples of newspapers and magazines from 1842 until today. Now, the pioneer of the Jewish press in our country is the weekly Şalom newspaper that was founded in 1947.

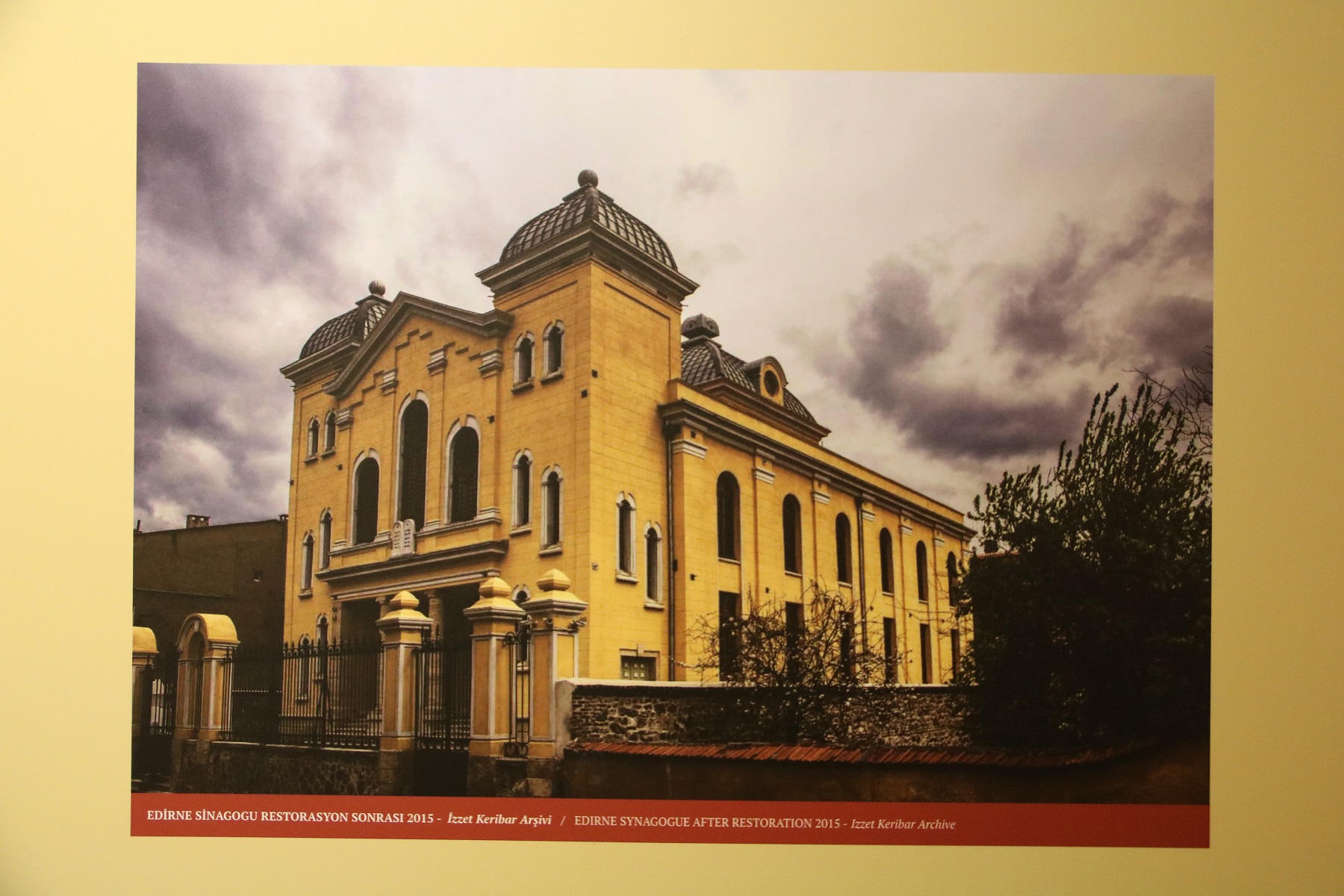

In the museum, there is a touch screen map where you can see all the synagogues and important places for Jews in Turkey. You can see here the holy places for Jews that are used and not used today. Most of them being in Istanbul, they are all over the country from Edirne and Izmir to Gaziantep and Antakya. There was a serious decrease in the number of Jews in our country, especially during the 20th century and one of the most striking examples of this could be seen in the story of the Edirne Synagogue.

It is the biggest synagogue in our country and it was built in the beginning of the 20th century. At that time, there was a Jewish community of about 22 thousand in Edirne. It is really sad that today there is only one Jewish person left living in Edirne. This precious synagogue was restored by the Directorate General of Foundations and reopened in 2015. A while ago, a wedding ceremony was organized in this synagogue by two families from Istanbul. Also in the museum, there is information on Karaite Jews who are coming from Turkic Tribes, who are not Jews but accepted Judaism. According to a thesis, the real name of Karaköy, one of the places where Karaite Jews were settled in Istanbul, was “Karay Köyü (Karaite Village)”.

As part of the events on November 27, I watched a representational Jewish wedding ceremony in Neve Shalom Synagogue. It was a very nice, modest ceremony where beautiful Jewish songs were played and sung.

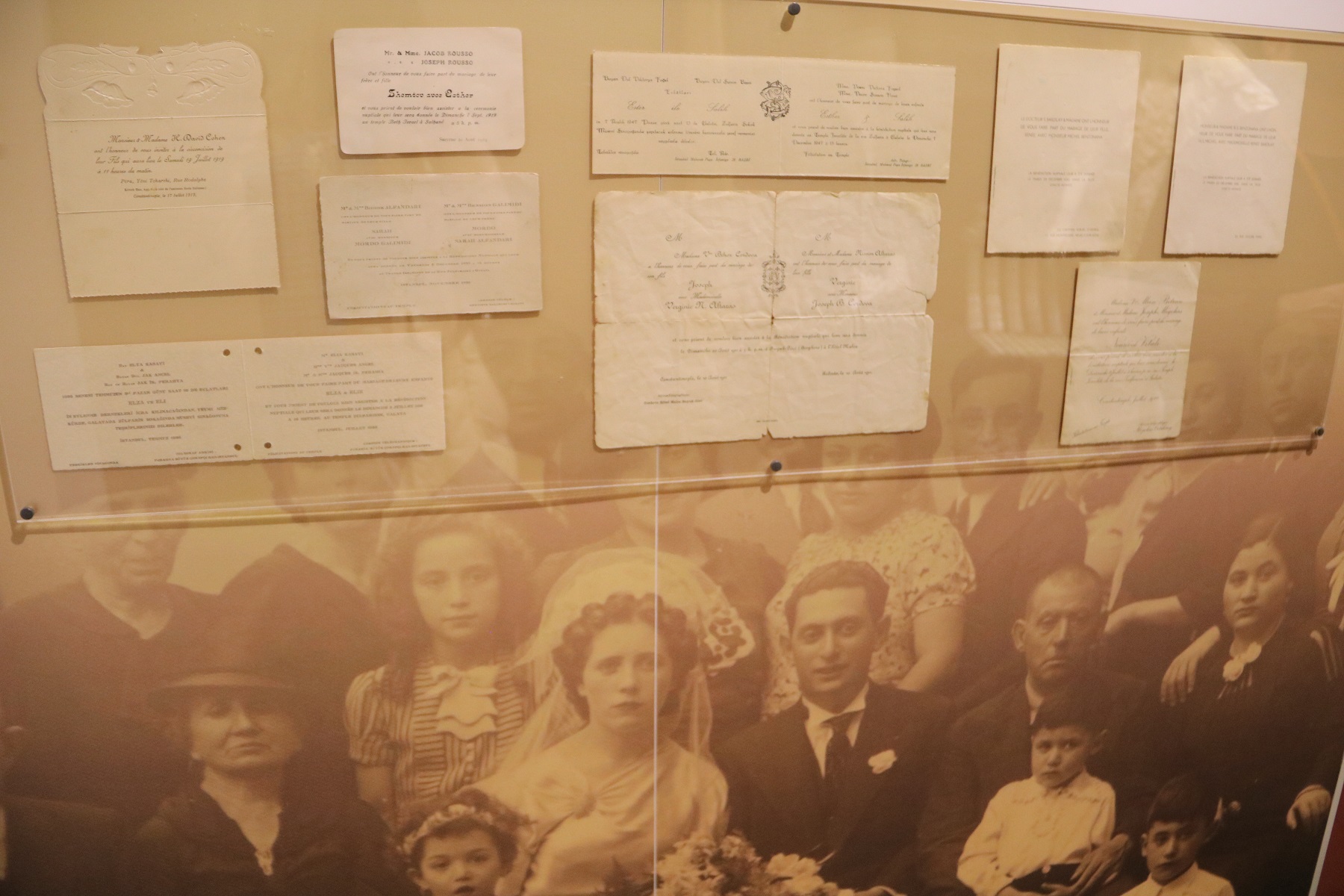

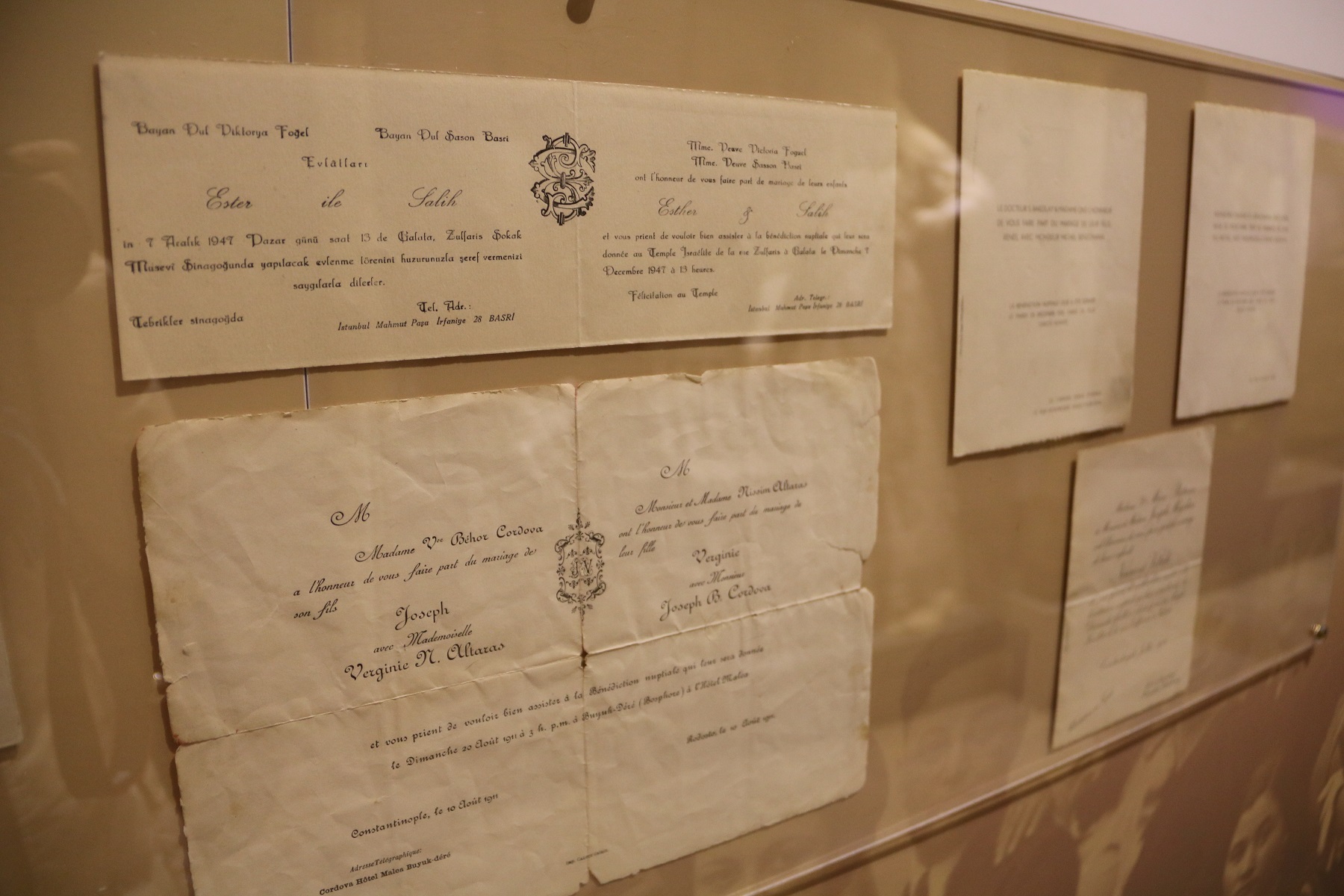

In the museum, you can see information, photographs and presentations on the wedding traditions and social life of the Turkish Jews from the Ottoman times until today.

The Jews living here were influenced by the Turkish culture. They have had unique traditions which do not exist in other Jewish communities of the world. For example, in the Ottoman times, Jewish families organized a henna night before the wedding just like Muslims. The same thing can also be seen in the clothes. The groom wearing a fez is an example for this.

In Jewish tradition, marriage is made under a roof. The bride and the groom sign a wedding contract called “Ketuba”. In Judaism normally a man can marry more than one woman, but for centuries with an item added to “Ketuba”, the groom promises that he would not marry another woman. In this way monogamy is ensured. This contract is signed in order to protect the woman’s rights and with the items added to it, marriage becomes more contemporary. In the old times, “Ketuba”s were hand made and decorated, but today they are printed documents.

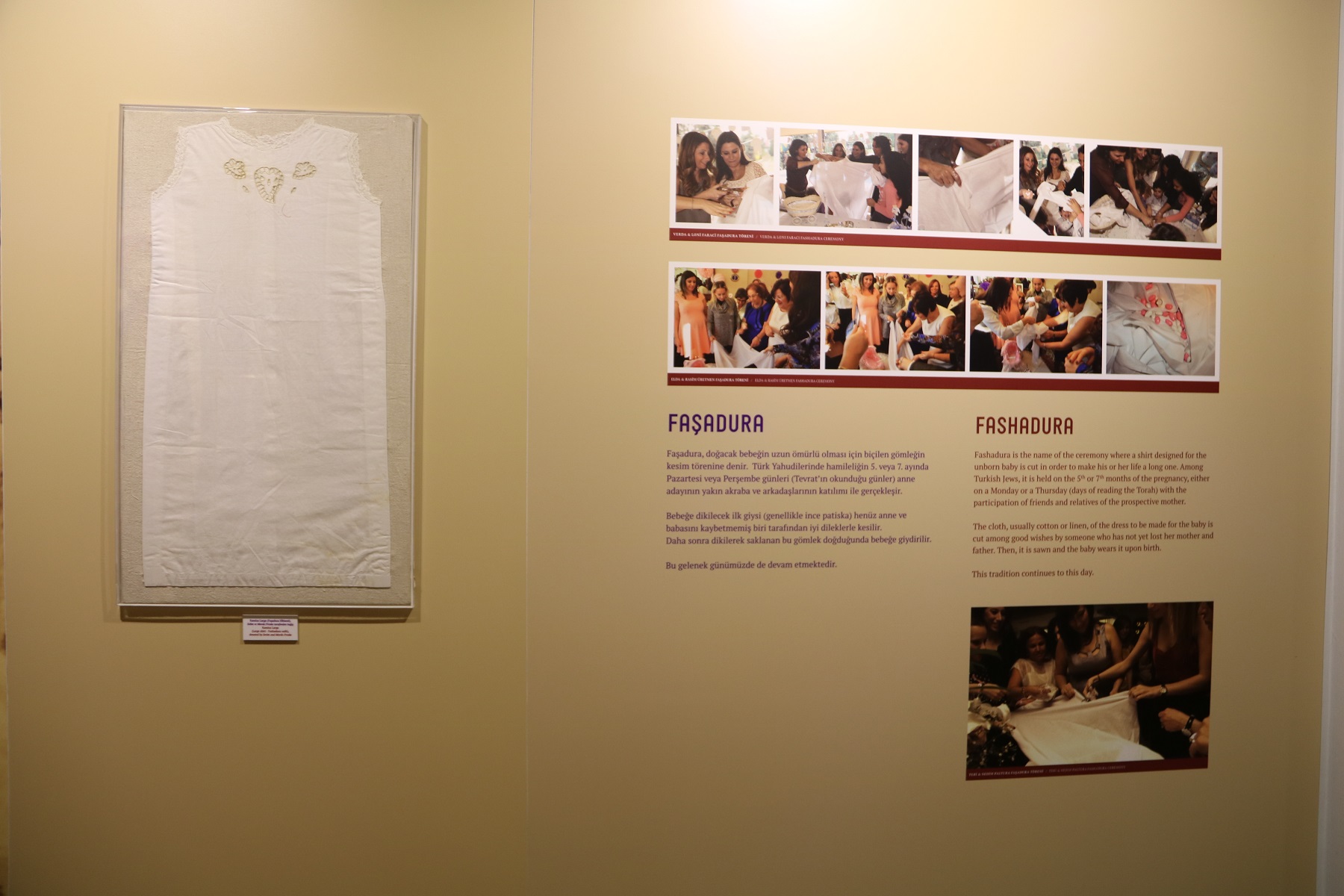

Amulets and charms that are believed to protect pregnants, puerperants and newborn babies are important in the Sephardic Jewish culture. Prayers are written on amulets such as crescent, blue eye, Star of David, menorah and hamsa. When the bride gets pregnant, in order for the baby to have a long life, in the 5th or 7th month of pregnancy, a ceremony called “Fashadura” is held, where the lady’s friends and relatives sew a dress for the unborn baby.

The influence of Turkish culture can also be seen in religious symbols and objects. Torah mantles, menorahs ve hanukkiahs (a nine-branched candelabrum lit during the holiday of Hanukkah) have been decorated with the shapes of crescent and star, and other Ottoman and Turkish motifs were used. Hence, these objects are like symbols of friendship and peace between people from two religions. I learned that these special hanukkiahs in the museum were exhibited in Europe before and attracted a lot of attention.

We can see the traces of intercultural interaction, also in the language of the Sephardic Jews, Ladino. Writer Mario Levi, in his seminar in the European Day of Jewish Culture said, “Now I will tell you a sentence in Ladino and all of you will understand”. In his sentence there were Turkish words for ferry (vapur) and dock (rıhtım) and we really did understand. Ladino language has the basis of the Spanish used 500 years ago. Through centuries it evolved in a natural way as a result of its interaction with Turkish and other languages spoken in this land such as Greek, French, Italian and even Portuguese. It survived until today, but unfortunately nowadays it is rarely spoken and not used by the young generation. Therefore it is facing the threat of extinction.

Mr. Roberto Sadacca is responsible for the visitors in the museum and is a Sephardic Jew himself. He says, “If a Spanish listens to us carefully, he/she can understand us, and we can understand him/her. Ladino’s basis is the Spanish of 500 years ago when we left Spain. However, because we did not much go to school before Alliance Israélite Schools were opened, we learned this language only by listening to our mothers and grandmothers. And a language without written rules and grammar is destined to perish and be forgotten.”

In the Ottoman State, until the middle of the 19th century many Jews were illiterate. Under the leadership of a group of French Jews who wanted to change this, Alliance Israélite Universelle Schools were opened in 1867. They were opened in many cities of the Ottoman State and the language of instruction in these schools was French. They contributed to educating the Ottoman Jews and thanks to these schools, new generations were educated. Later on they were closed. There were also some non-Jewish students who studied in these schools and one of them was, Turkey’s 3rd President, Celal Bayar. Today, there is only one Jewish school in Turkey, The Ulus Jewish School, which is secular.

Mr. Sadacca explains: “Since the 1980’s, Ladino started to die. This happened naturally by itself, because more and more people started to go to the universities and learn Turkish properly. I think they preferred Turkish. This was a natural selection. Only certain people have an interest in modern Spanish. There is no such interest in the general community. And I think, there is no reason for it to be. Because our homeland is Turkey.”

“What we want the most is that they leave our museum with positive feelings about Turkish Jews”

Mr. Sadacca is a chemical engineer and has been working in the museum since it was moved to its current location. He says that he is happy to introduce their culture to the visitors and he thinks this is an honourable job: “The goal of this museum is to introduce the Jews in Turkey to the Turkish society and the world. I often hear the following reaction from our Turkish visitors: ‘we are so much alike’. Well, this is our purpose. At the end of the day, we have so much in common and it is very important to show this. There are so few Jews in this big country. And also because they don’t show themselves very much, many Turkish people have not met a Jewish person in their lives. As a result of our efforts, we hope that they can know more about us and like us more. We want from our visitors to learn as much as possible from what we are trying to provide here. What we want the most is that they leave our museum with positive feelings about Turkish Jews.”

I think their efforts are being useful. A museum can change a person’s point of view significantly. And with time, some things may change. There is hope for that. Each time I visited the museum, I also heard the words “we are so much alike” around me. First I thought that too but then I asked myself, “after all, was it possible that we were not alike?” We have been living in the same land for centuries and sharing the same homeland. In my opinion, if we were not alike, that would be surprising. One of the moments I felt this most strongly was when I heard the song “My country is like no other… (Bir başkadır benim memleketim…)” in the European Day of Jewish Culture. It is a unifying song that everybody knows in Turkey. Did you know that this song is a Jewish folk song? The cultures of people who have lived together in the same land for centuries are so evolved together and intertwined that it is impossible to break them apart. Most particularly, it is impossible to understand the hostilities. I hope that there will always be friendship, love and peace between people.

Our country is really “like no other”. It is a country where there has been a lot of intercultural interaction for so many years and many different cultures have mixed and combined. Whatever we have today that we like and are proud of, they have been shaped thanks to the contributions of people from various different cultures. We should never forget that we owe our beauty to this! By leaving the unpleasant experiences behind and building further layers on top of the positive ones, uniting, glorifying the different cultures in this country and living in peace is our responsibility. Everyone should visit this museum to feel this. This country belongs to all of us. Perhaps more events could be held in the museum and by this way more people could be attracted. Especially the food and music has the power to attract, in my opinion. I end my words with the recipe of Pandispanya (Yellow Cake). It is usually made with lemon and it means “Spanish bread”. Wishing friendship and peace, enjoy!

PANDISPANYA (YELLOW CAKE)

Ingredients:

5 eggs

1 1/3 cups flour

Zest and juice of one lemon

1 1/3 cups sugar

1 teaspoon baking powder

Instructions:

Beat the eggs and sugar until frothy. Gradually add the flour and baking powder. Mix in the zest and juice of the lemon, and pour into a greased pan. Bake it in 180° preheated oven for 40 minutes. (Check with a toothpick to see if the cake is done.)

Reference for the recipe: “Sephardic Cook Book” by Viki Koronyo and Sima Ovadya

Additional Reference: “The Historic Synagogues of Turkey” by Joel A. Zack

(A shorter version of my article was published on hurriyet.com.tr in Turkish. Please click here to read it)